By: John M. Grondelski

PERTH AMBOY – April 29 marks the 75th anniversary of U.S. forces liberating the Dachau concentration camp. Less than two weeks before Germany’s surrender, the 45th Infantry Division of the U.S. Seventh Army freed the camp, just outside Munich. Upon liberation, they found more than three dozen box cars with corpses outside the camp and barracks inside the camp equally stuffed with the dead and the dying.

Dachau was the first Nazi concentration camp, opened in 1933. Long into the postwar period, it epitomized “concentration camp” for most Americans, perhaps because—unlike Auschwitz, liberated by the Soviets—it was American forces that freed the camp and American journalists that displayed its horrors for Americans to see.

Dachau was a particular hell for clergy: over 2,700 of them, most of them Catholic, many of them Polish, were held in the camp. Nazism was an enemy of religion, particularly Christianity. Catholic priests in countries under German occupation were brutalized. Polish Catholic clergy were decimated during the War, for they had to contend with two atheist totalitarianisms intent on strangling the spiritual in their country: Hitler’s Nazis and Stalin’s Communists, both of whom invaded Poland in 1939.

Polish religious orders, including the Franciscan Capuchins, suffered heavy losses. By 1940, many were in concentration camps. Dachau was the most common destination, so much so that a clandestine, underground seminary that produced new priests even operated in its barracks.

When the War ended, some of those Capuchins decided to remain in the West rather than return to a Poland over which an Iron Curtain was falling. One of them eventually made his way to Perth Amboy. But not first without a detour to Oklahoma.

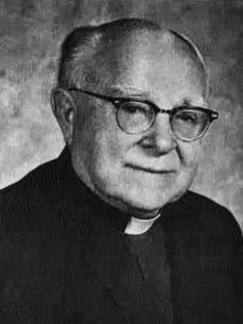

Władysław Lechański was born in August 28, 1908 in Zuski, in central Poland. He entered the Capuchins in 1926, taking the name in religion “Alexis.” Fr. Alexis studied philosophy in Holland then returned to Poland for his seminary studies in theology. He was ordained a priest on June 14, 1934. He earned the equivalent of master’s degrees in moral theology and Church law at the Catholic University of Lublin, and had a promising career ahead of him as a teacher of canon law. He lived at the Capuchin monastery in Lublin, Poland, a beautiful university town about 110 miles south of Warsaw, when World War II broke out.

He was arrested by the Gestapo on January 25, 1940, along with 25 other Capuchins then living in the Lublin monastery. At first, he was detained in the notorious Gestapo prison located in the Lublin Castle then, in June, was transferred to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin. His final move was in December 1940, when he was sent to Dachau. He was a prisoner of Dachau for four years and four months. He became Number 22639.

When American troops liberated Dachau, Fr. Alexis remained in the West. He went to Paris, apparently in the hope of continuing his studies in law. (He was said to have taught canon law in the “underground seminary” that the priests of Dachau conducted at night, training vocations to the priesthood that came out of that hell). His Capuchin superiors asked him to go to the United States to try to raise money for the Polish monasteries destroyed during the War, so Fr. Alexis traveled to Ireland to learn English while waiting for his U.S. visa, which finally came in 1947. He arrived in New York July 2, 1947, spending some time leading a retreat for Felician Sisters in Buffalo and residing at the Capuchin parish of St. John’s in Manhattan, just outside Madison Square Garden. That’s where the Oklahoma detour came in.

The Catholic bishop of Oklahoma City-Tulsa was in need of priests. He had established a parish in the 1930s, St. Ann’s, in Broken Arrow. The area was a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity, where Catholics were unwelcome. The first pastor left to become a World War II chaplain. The bishop needed priests; Fr. Alexis went to Oklahoma and became St. Ann’s pastor.

Five of the Polish Capuchins’ “Class of Dachau” eventually passed through Broken Arrow: Fathers Alexis Lechański, Hyacinth Dabrowski and his brother Robert, Wacław Karas, Jan Salwowski, and Rafal Nienaltowski. Capuchins were responsible for that parish until 1996.

But the Sooner State, with few Catholics and fewer priests, also had few Polish Americans, and these priests also wanted to work with their fellow countrymen. Gradually, then, many made their way back east, to staff Polish American Catholic churches in New Jersey and in New York. The “class of Dachau” eventually served in Polish American parishes in Bayonne, Laurence Harbor, Manville, New Brunswick, Passaic, Paterson, Perth Amboy, and Trenton, Father Alexis arrived at St. Stephen’s (now St. John Paul II) Church on State Street ca 1970. He remained there until his departure was forced for health reasons in the mid-1980s. He died in 1988 and is buried in the Capuchin plot at Sacred Heart Cemetery in Manville.

One remaining artifact of the Polish Capuchins who served the Catholic Church in New Jersey is St. Stanislaus Friary in Oak Ridge, in Jefferson Township near Sparta. As members of a religious order, the Capuchins wanted to retain their communal life and the Friary—which had originally been constructed by Alfred T. Ringling of circus fame, who lived there until 1919. The last of the Dachau Capuchins died in 2010, but Oak Ridge remains alive under the care of a modern day Polish Capuchin, Brother Jerzy Krzyśków. He can be contacted at jkrzyskow@yahoo.com or 1-908-922-6396 and would love to hear from those with memories of the priests from Dachau.

I vividly remember Fr. Alexis walking around the backyard of the rectory at now St. John Paul II Church, praying his Rosary in the evening twilight. He was regularly in the confessional at that parish, and served that parish until his health failed. As New Jerseyans recall the anniversary of Dachau’s liberation, let’s not forget: one of its survivors served Catholics in our own city by the bay.