January 1865

By Phil Kohn

Phil Kohn can be reached at USCW160@yahoo.com

On New Year’s Day, 1865, Union soldiers, trying to clear Arkansas of its multiple guerrilla bands, engage in a skirmish with Confederate irregulars near Bentonville, in the northwest corner of the state.

In Savannah, Georgia, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman on January 2 begins preparing to move his army northward into South Carolina. He orders the transfer of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s east wing of his force to Union-held Beaufort, South Carolina. His west wing, commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum, is arrayed along the south bank of the Savannah River. Waiting for them in South Carolina are some 10,000 Confederate troops under Lt. Gen. William Hardee.

As Maj. Gen. Howard’s troops begin moving toward their destination of Beaufort, South Carolina, on January 3, skirmishing breaks out at Hardeeville, around 21 miles north of Savannah.

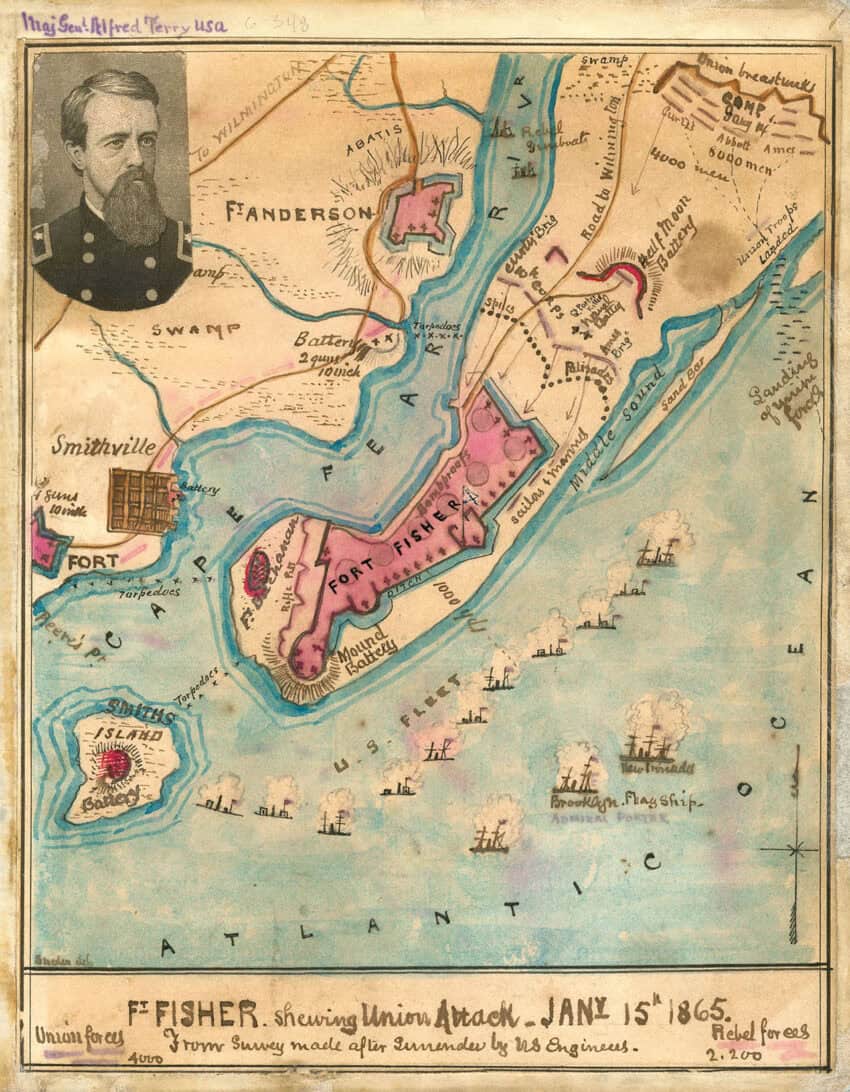

In hopes of making up for the disastrous expedition in December — led by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler — against Confederate-held Ft. Fisher, near Wilmington, North Carolina, a second Union armada departs from Bermuda Hundred and City Point, Virginia, on January 4. This time, the 8,000 soldiers aboard — most of them veterans of the first operation —are under the command of Maj. Gen. Alfred H. Terry, a sound and skillful military leader.

On January 6, Jefferson Davis writes a long and contentious letter to Alexander Stephens, his outspoken and often-critical vice president, chiding him for actively working to undermine the people’s confidence in Davis. Stephens, involved in his native Georgia’s peace movement, has alleged that Davis secretly favored Lincoln (who would continue the war) over McClellan (who would likely seek peace) in the recent Northern elections. In Arkansas, Union troops clash with Confederate guerrillas at Huntsville.

In Washington, D.C., the War Office on January 7 — at the request and suggestion of Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant — issues orders relieving Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler of command of the federal Army of the James and the Department of Virginia and North Carolina. Maj. Gen. Edwin Ord is named to replace him. In Virginia, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan releases more of his troops in the Shenandoah Valley to join those besieging Petersburg, south of Richmond. In Europe, with the Danish-Prussian War (February 1, 1864 – October 30, 1864) recently ended, the formidable Danish ironclad ram Sphinx departs Copenhagen for Quiberon Bay, France. The Confederate government has already secretly purchased the vessel, which will become CSS Stonewall. (Although designed to operate in relatively calm waters, Stonewall — after being fitted out in Bordeaux, France — successfully navigates the wintry North Atlantic Ocean, first landing at Nassau, the Bahamas, and then, finally, arriving at Havana, Cuba, in April. There, finding that the Civil War is coming to an end, Stonewall’s commander, Capt. Thomas J. Page, CSN, sells the vessel to Cuba’s Spanish government to pay off his crew. After the war, the U.S. government purchases Stonewall from Spain and, in 1867, sells it to the government of Japan. Renamed Kotetsu (meaning “ironclad” in Japanese), it becomes the first ironclad warship of the Imperial Japanese Navy.)

On January 8, the ships carrying Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry’s 8,000 Union troops rendezvous with a large flotilla of vessels commanded by Adm. David Porter off the coast of Beaufort, North Carolina, about 75 miles northeast of Wilmington and its protector, Ft. Fisher, on the coast.

Retreating from Nashville, the remaining soldiers of Gen. John Bell Hood’s Confederate Army of Tennessee reach Tupelo, Mississippi, on January 9. Senior officers begin trying to reorganize the broken army. Word comes from Richmond that President Davis is hoping to transfer some troops eastward, to assist Lt. Gen. William Hardee oppose Sherman’s Union force in the Carolinas. In Savannah, Georgia, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton meets with Maj. Gen. William Sherman to discuss military strategy.

U.S. Maj. Gen. George Thomas on January 10 moves his army on a southwest-to-northeast line stretching from Eastport, in northeastern Mississippi, to Clifton, Tennessee, southwest of Nashville. In Missouri, Union soldiers battle Confederates near Glasgow, in the north-central part of the state. In Washington, D.C., the debate in the House of Representatives gets more intense over the proposed Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution that would abolish slavery in the U.S. (The amendment has already passed in the Senate.) Although Union-Republicans (generally favoring the amendment) have won a House majority in the recent elections in November, those representatives won’t be seated until December 1865. Republicans are anxious that the House pass the Amendment before then, so it can go to the states for ratification. (To become law, the Amendment would need three quarters, or 27, of the 36 states to ratify it.) The Republican mission is to get enough Democrats to change their votes to pass the amendment in the house during this session of Congress to send the amendment to the states. Moses Odell, a Democrat from New York and a member of the U.S. Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, comes out in favor of the amendment. However, a fellow New York representative, Fernando Wood, former mayor of New York City and chairman of the powerful House Committee on Ways and Means, declares his opposition, arguing that the amendment would destroy any chance of making peace with the South.

Having departed Staunton, Virginia, on January 7, with 300 cavalrymen, and riding in icy cold weather and through deep snow, Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser on January 11 makes a surprise attack against the 1,500-man Union garrison at Beverly, West Virginia, located in a strategic position astride the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. Killing or wounding 25 Federal soldiers during the one-sided, 30-minute fight, Rosser hauls off 583 prisoners. Most of the uncaptured Federals (including 200-plus prisoners who escape from their captors) skedaddle to Buckhannon, West Virginia, some 25 miles to the northwest. From Virginia, U.S. Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant — calculating that Gen. Hood, in Mississippi, won’t move his Confederates, and that if he does, Maj. Gen. Thomas would not pursue him aggressively — decides he can better use some of Thomas’s troops in the East. Accordingly, some 23,000 soldiers of the U.S. XXIII Corps, under the command of Maj. Gen. John Schofield, depart Clifton, Tennessee, heading east.

On January 12, Maryland politician Francis Blair, a Democrat, meets secretly in Richmond, Virginia, with Jefferson Davis to discuss possible avenues of peace between the U.S. and the Confederacy. Although he is a private individual with no official portfolio, Blair apparently has the sanction of President Lincoln. Davis gives Blair a letter to be given to Lincoln that indicates that Davis is willing to enter peace negotiations, and the Confederate president agrees to send a commission to meet with President Lincoln on February 3rd to discuss possible peace. On the military side of things, Davis sends a message to Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, who commands the Confederate Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, to send troops from Tupelo, Mississippi, to reinforce Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s force opposing Sherman’s Union troops in the Carolinas. Davis advises Taylor to keep some troops in the West to hold Union Maj. Gen. Thomas in check, but the main part of what is left of the Army of Tennessee should be sent eastward “to look after Sherman.” On the same day, Adm. Porter’s Union flotilla reaches Ft. Fisher, which protects Wilmington, North Carolina. Gen. Braxton Bragg, now in charge of Wilmington-area Confederate defenses, moves 6,000 troops under Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke to the north end of the island on which Ft. Fisher stands.

January 13 sees much action. Gen. John Bell Hood resigns as commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee; Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor is named to replace him, under Gen. Pierre Beauregard as overall commander. Off North Carolina, Adm. Porter’s flotilla — 59 ships with 627 guns — begins a bombardment of Ft. Fisher shortly after midnight. The fort’s commander asks Gen. Bragg to send troops to reinforce the 1,500 men in the fort; Bragg doesn’t and keeps Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke’s men on the north end of the island. Under cover of the naval bombardment, Maj. Gen. Terry disembarks 6,000 Union troops from Porter’s ships and lands them — unopposed — north of Ft. Fisher. They spend that day and the next digging in between the fort and Hoke’s men.

Col William Lamb, commanding the still-under-bombardment garrison of now badly damaged Ft. Fisher, on January 14 sends an urgent request to Gen. Braxton Bragg to have Maj. Gen. Hoke’s troops — on the north end of the island on which Ft. Fisher is located — attack the sizeable Union force digging in north of the fort. In Arkansas, Confederates assault a Union stockade at Dardanelle, in the northwestern portion of the state.

On January 15, 2,261 U.S. sailors and marines make an amphibious landing against the seaward side of Ft. Fisher. Fighting is vicious, and the Federals are forced back to their boats. While the Confederates are preoccupied by the seaborne attack, Gen. Terry sends 3,300 men against the northern face of Ft. Fisher, leaving the remainder of his troops to prevent Hoke’s Confederate force from interfering in the battle. Terry’s troops break through and, after fierce fighting, carry the fort. Despite several appeals to Bragg for reinforcements or aggressive action, Bragg never responds with any troops. In the fighting, the U.S. suffers around 1,341 casualties (killed, wounded, missing); the Confederates lose around 500 men, killed or wounded. Some 1,900 Confederates are taken prisoner, including Maj. Gen. William Whiting, commanding the Department of North Carolina (he had moved into Ft. Fisher when it came under siege) and Col. Lamb, the fort’s commandant. Both men later strongly vilify Braxton Bragg for his failure to attack Terry’s landing party. Bragg claims Terry’s defensive line was too strong. The bottom line: Although Wilmington, some 21 miles farther up the Cape Fear River, is still in Confederate hands, it is now cut off as a blockade-running port — the last in the Confederacy.

As a way of providing for the roughly 10,000 black refugees that have been following his troops through Georgia on his “March to the Sea” and then into South Carolina, Maj. Gen. Sherman on January 16 issues “Field Order #15,” which creates a 30-mile-wide preserve for the settlement of blacks in a strip of land along the coast, including islands, that extends from Charleston, South Carolina, to northern Florida. Each family is to get 40 acres to farm. In Washington, D.C., Francis Blair reports on his meeting with Jefferson Davis to President Lincoln, who agrees to have a representative meet with the Southern “peace delegates.” At Ft. Fisher, North Carolina, two drunken U.S. sailors, seeking souvenirs, blunder into a magazine with lit torches, detonating 13,000 pounds of gunpowder, killing 25 and wounding 66 Union personnel. Some 110 Confederates, captured during the previous day’s battle, are also killed in the explosion. Hearing of the loss of Ft. Fisher, President Davis sends a message to Gen. Bragg to retake the fort if possible. The Confederate Senate, in a move challenging President Davis’s control over military matters, passes a resolution advising Davis to: 1) appoint Gen. Robert E. Lee as general-in-chief of the Confederate Army; 2) restore Gen. Joseph Johnston as commander of the Army of Tennessee; and 3) name Gen. Pierre Beauregard as overall commander in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina.

On January 19, Maj. Gen. William Sherman begins moving the west wing of his army northward into South Carolina. Heavy rains begin to fall, which will hold up, and sometimes stop, their progress. With much reluctance on his part, and significant prodding from President Davis, Robert E. Lee agrees to take on the position of general-in-chief of the Confederate Army, effectively the military commander of all Confederate forces. He will, as well, continue to command the Army of Northern Virginia.

While many of his men remain in Savannah, Georgia, waiting to move north, Maj. Gen. William Sherman on January 21 moves his headquarters out of the city and into South Carolina, towards Beaufort, on the coast.

Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor officially assumes command of the Army of Tennessee on January 23. Because many soldiers have been shipped east to help defend against Sherman’s advance, Taylor’s command numbers barely 18,000 men. In Virginia, 11 Richmond-based Confederate ships try to run past Union forts along the lower James River in an attempt to scatter the Federal blockading squadron and to destroy the Union supply depot at City Point. Four of the vessels run aground and the Confederate Navy aborts the operation.

On January 24, Maj. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest assumes command of the Confederate Department of Mississippi, East Louisiana and West Tennessee. It includes a 10,000-man cavalry corps.

The Confederate cruiser CSS Shenandoah arrives at Melbourne, Australia, on January 25. After a short stay for refit and resupply, she heads out for the North Pacific Ocean to attack the U.S.-flagged fishing and whaling fleets.

Fighting breaks out between Union and Confederate troops on January 27 in DeKalb County, in northeastern Alabama. In Richmond, Gen. Robert E. Lee points out the “alarming frequency of desertion” in the Confederate Army. He says the per-soldier “ration is too small” and feels the Commissary Department could do better.

Jefferson Davis on January 28 appoints three commissioners to the coming C.S.-U.S. peace talks: Vice President Alexander Stephens; Robert Hunter, President pro tempore of the Confederate Senate; and Assistant Secretary of War John Campbell, a former justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. Davis instructs them that Southern independence is to be the only basis upon which negotiations may proceed. Skirmishing breaks out between advance elements of Sherman’s troops and defending Confederates along the Combahee River in the Lowcountry region of southeastern South Carolina.

The Confederates are pondering on January 29 just where in South Carolina Sherman’s Union troops will be headed once they get rolling. From the Federals’ presence on the coast at Beaufort, the target seems to be Charleston. However, the bulk of Sherman’s force is still at or around Savannah, Georgia.

President Lincoln issues passes for the three Confederate commissioners, allowing them to pass through Federal lines to Union-held Fort Monroe, at the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula. Some 4,000 Confederate troops sent eastward from Mississippi by Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor earlier in the month arrive at Augusta, Georgia, on January 30.

On January 31, in Richmond, Robert E. Lee is officially named commander-in-chief of all Confederate armies. The move is too little, too late and effectively has no impact. In Washington, Abraham Lincoln informs Secretary of State William Seward that he is to proceed to Fort Monroe and meet with the Confederate peace commissioners on February 3. Regarding the conference, Lincoln insists that recognition of Federal authority must be a precondition for any further negotiations. (This is, of course, at complete odds with Jefferson Davis’s instruction to his delegates that negotiations continue only on the basis of Confederate States independence.) In the U.S. Congress, the House approves the 13th Amendment to the Constitution (abolishing slavery), 119-56, with 8 not voting. The Senate already having approved the measure, Lincoln signs it. If and when ratified by three quarters (27) of the 36 states in the Union, the Amendment will become the law of the land.