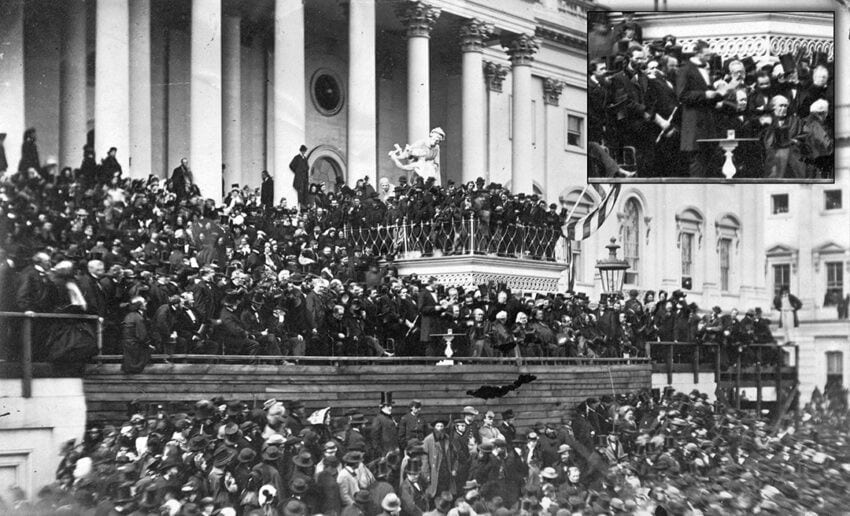

President Lincoln, at the podium (inset), delivering his Second Inaugural Address. Click on photo to enlarge. (wikipedia/Public Domain)

March 1865

By Phil Kohn

Phil Kohn can be reached at USCW160@yahoo.com

On March 1, 1865, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Union force continues to march northward into North Carolina, with only localized skirmishing slowing his progress.

At Waynesborough, in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, 5,000 of Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s U.S. cavalrymen under Brig. Gen. George A. Custer on March 2 engage the remaining 1,200 Confederate troops of Lt. Gen. Jubal Early. The Southerners are trounced, losing 200 wagons and over 1,000 men taken prisoner. Early, his staff and a small number of soldiers escape and make their way back to Richmond. The Battle of Waynesborough marks the end of the last campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. Gen Robert E. Lee sends a letter through the lines to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, suggesting that the two of them meet and hold a “military convention” to try to reach “a satisfactory adjustment of the present unhappy difficulties.” Lee’s move is spurred by a meeting held on February 21, 1865, between Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet and Union Maj. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord, the newly named commander of the Army of the James. Both men are old friends from their West Point days. In the meeting, Ord references the failed peace conference that was held off Fort Monroe in early February. He suggests to Longstreet that since the politicians could not — or would not — negotiate for a cessation of hostilities, perhaps senior military leaders could get the job done. Ord proposes bringing Grant and Lee together to talk and, perhaps, become the instruments of peace. Ord leaves Longstreet with the feeling that Grant might be open to such an overture.

The U.S. Congress establishes the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. The Bureau will have overall supervisory authority over all those in the South dislocated by the war and needing temporary assistance. A large part of its efforts will go toward aiding and providing work for the newly freed black population. President Lincoln, having been advised of the peace overture made to Lt. Gen. Grant by Gen. Lee, informs Grant that he is to have no conference with Lee unless it is to accept the surrender of his army. Lincoln makes clear to Grant that all political issues are to be settled only by him personally.

In Washington on March 4, Abraham Lincoln takes the oath of office for his second four-year term as president. His Second Inaugural Address includes phrases that signal his vision of a conciliatory post-war reconstruction: “With malice toward none; with charity for all.” On the battlefield near Petersburg, Lt. Gen. Grant notifies Gen. Lee that he has no authority to hold such a conference as has been requested and that there has been some sort of a misunderstanding. In Richmond, the Confederate Congress authorizes a revision to its national flag. The standard, to be known as “The National Flag, Third Pattern” will add a vertical red band to the end of the current Second National Flag, referred to as “The Stainless Banner.” That flag has a solid white field with the so-called “Southern Cross” (the battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia) in its canton. The idea of the newly added red band is to make the national flag look less like a flag of surrender on the battlefield.

In North Carolina, on March 6, U.S. troops under Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox work to repair rail lines running between New Berne, near the coast, to Goldsboro, some 60 miles to the northwest. Cox and his superior, Maj. Gen. John Schofield, intend to link up with Sherman’s troops at Goldsboro, and their hope is that the restored railroad will allow supplies to be transported from the coast. At Kinston, North Carolina, roughly midway between New Berne and Goldsboro, some 5,000 Confederate reinforcements arrive from Tennessee. Gens. Braxton Bragg and Joseph Johnston hope to use these troops, along with those under Bragg’s command, to attack Cox’s men, moving westward from New Berne.

Kinston, North Carolina, is the site of a three-day battle that begins on March 8. Around 9,000 Confederate troops under Gen. Braxton Bragg and Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke engage some 13,000 Federals under Maj. Gen. John Schofield who have come north from Wilmington. The Confederates hold their own on the first day, but each succeeding day finds more Federal reinforcements present. In the North, on March 8, Vermont becomes the 19th state (of 27 required) to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which will ban slavery in the nation.

Confederate cavalry under Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton and Lt. Gen. Joseph Wheeler launch a surprise attack on Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s Union cavalry, bivouacked at Monroe’s Crossroads, North Carolina, late in the evening of March 9. Many Yankees are captured in their beds. Kilpatrick, unpopular on both sides — by his own men because of the way he relentlessly pushes them to the extreme (their nickname for him is “Kill-Cavalry”), and by the Confederates because of his eager and wanton destruction of their property — is spending the night with a mistress in a nearby log cabin and is almost captured. He barely eludes his captors by running away dressed only in his nightshirt. Kilpatrick does manage to rally his men, however, and they finally beat off the Confederate attack. The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads comes to be known unofficially as Kilpatrick’s Shirttail Skedaddle.

Finally withdrawing from the Battle of Kinston, North Carolina, Gen. Bragg orders a retreat to Goldsboro, North Carolina, some 30 miles away, and then a further move to Smithfield, North Carolina, 25 miles farther to the northwest. Bragg’s idea is that he will there join with Gen. Joseph Johnston’s (newly reconstituted, yet ragtag) Army of Tennessee.

The main body of Maj. Gen. Sherman’s force arrives at Fayetteville, North Carolina, on March 11. The troops will rest there for a couple of days. While the main action is occurring in Virginia and the Carolinas, fighting — and dying — continues in other parts of the country. West of the Mississippi River, there is skirmishing at the Little Blue River, in Missouri, and at Washington, Arkansas.

At Fayetteville, North Carolina, Sherman’s troops busy themselves on March 12 destroying machinery and transportation equipment that might be of use to the Confederates. There is skirmishing in Virginia, Louisiana and Missouri.

The Confederate Congress on March 13 finally passes a bill permitting blacks to fight in the Confederate Army. President Davis immediately signs it into law, and mustering-in and training of slaves and free blacks begins. By month’s end, black Confederate soldiers are seen on Richmond streets. The law stipulates, however, that slave soldiers cannot be freed “except by consent of their owners and the states in which they reside.”

The Confederacy suffers a political setback on March 14, when British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston informs Confederate envoys in London that Great Britain will not recognize the Confederate States as an independent nation. In North Carolina, Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox’s Union soldiers reach Kinston. They are continuing to repair railroad tracks from New Berne, North Carolina, on their way to Goldsboro, to link with Sherman’s army.

Maj. Gen. Sherman moves his troops northeastward out of Fayetteville, North Carolina, towards Goldsboro, on March 15. Fighting erupts along his advance. His army moves in three columns, the left commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum, moving north in a feint towards Raleigh. Gen. Johnston is concentrating his forces north of Sherman, hoping to attack and best the three Union columns individually before they can unite.

The troops of Sherman’s left column, under the command of Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum, and Johnston’s Confederates, under the command of Lt. Gen. William Hardee, clash at Averasborough, North Carolina, on March 16. Although the battle is small and casualties relatively light (U.S: 682; CS: 865), Sherman notes that it is the first major resistance to his march. Hardee joins Johnston at Smithfield, North Carolina, some 23 miles to the northeast. In the North, New Jersey rejects ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, which would ban slavery in the U.S. The vote, taken in the State Senate, is 12 nays, 8 ayes and one absent or abstained.

On March 17, U.S. Maj. Gen. Edward Canby begins a campaign to take Mobile, Alabama. Canby plans a two-pronged assault: one column will approach from the east, from Pensacola, Florida; the other will move up the east shore of Mobile Bay from the south.

Brig. Gen. James Wilson on March 18 leads 14,000 U.S. cavalrymen from Eastport, Mississippi, into Alabama. The target: a Confederate munitions factory at Selma, some 230 miles to the south. Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s 6,000 Confederates are in their path but will have difficulty opposing Wilson’s huge force. At Mobile, Alabama, some 1,700 Federal troops move to the west shore of Mobile Bay, in an effort to deceive the Confederate defenders that the Union assault will come from that direction. In North Carolina, Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s column of Sherman’s Union force approaches Bentonville, where it receives heavy resistance from Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton’s Confederate cavalry. Hampton is trying to slow the Union advance to give Gen. Joseph Johnston time to concentrate his forces at Bentonville.

At Bentonville, North Carolina, Sherman’s and Johnston’s armies clash, on March 19. Slocum’s column pushes Hampton’s Confederate cavalrymen back, but then are counter-attacked by 20,000 of Gen. Johnston’s men. The Federals are forced to fall back and begin hastily entrenching. The Union troops repulse several full-scale attacks before night falls and ends the actions. As word of the fighting reaches Sherman’s center column, led by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, it swings westward to join the fray. Gen. Johnston, having failed to clear the field of the enemy, orders his Confederates to fortify their positions.

By the next day, Johnston’s 21,000 men are fighting almost 60,000 of Sherman’s (the forces of Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum and Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard). Johnston had hoped to defeat Slocum’s 30,000 before Union reinforcements could arrive, but it was not to be. Some skirmishing takes place, but neither side launches a full assault. In Knoxville, Tennessee, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman leads 4,000 Union cavalrymen eastward into North Carolina. His mission is to destroy enemy transportation lines and then link up with Sherman.

On March 21, Sherman’s Federals make several frontal attacks against the Confederates at Bentonville, North Carolina. At one point, Sherman sends a force to go around the battlefield and get into Johnston’s rear, cutting off any retreat route. Johnston detects the maneuver, and his men thwart the Union move while his main lines fend off the frontal Federal attacks. One reason for Johnston’s success is that while his force is outnumbered 3 to 1 in total, only about 16,000 of each side are engaged in the actual fighting. The battle lasts through the day, and, at night, Johnston orders a Confederate retreat to Smithfield, North Carolina, about 15 miles to the north. Over the three days of the battle, casualties are: U.S.: 1,646; C.S.: 2,606.

In northern Alabama, Union Brig. Gen. James Wilson’s 14,000 cavalrymen continue on their southward move on March 22, harassed only sporadically by Confederate defenders. Their target, Selma, is one of the last of the Confederacy’s munitions-manufacturing centers.

President Lincoln, accompanied by his wife Mary and his son Tad, on March 23 departs Washington for City Point, Virginia, which has become the main depot for the Union siege of Petersburg. In addition to providing insight into the military situation, Lincoln hopes the planned three-week trip will provide some rest and relaxation for him and his family. Moving on from Bentonville, North Carolina, the left and center columns of Sherman’s army reach Goldsboro, North Carolina. There, they link up with Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s column, which has arrived from the coast. Sherman’s march from Savannah, Georgia, to Goldsboro, North Carolina, has covered around 400 miles and has taken 50 days. Gen. Joseph Johnston places Confederate blocking forces on the two main routes that he figures Sherman will take on his way into Virginia: at Raleigh and at Weldon, farther east. Johnston calculates that positioning his men at these points will also ease his linking with the Army of Northern Virginia should Lee abandon Petersburg.

At Petersburg on March 24, Gen. Lee devises a plan to attack the right of the Union’s lengthy siege line, at a fortified position known as Fort Stedman. His thinking is that if he can capture Fort Stedman, he might break the Union supply line from City Point, possibly forcing Grant to contract his lines, which are not only stretching his Confederate defenders very thin but present problems if Lee wishes to move westward from Petersburg.

At 4:00 a.m. on March 25, 11,500 Confederates under Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon attack Union-held Fort Stedman outside of Petersburg, Virginia. Catching the Federals off-guard, the fort and about 2,000 feet of trenches on either side of it are quickly captured. However, no follow-on troops are available and Union reinforcements counterattack and regain all the lost ground, including the fort itself. By 7:45 a.m., the fight is over. U.S. casualties number around 1,500; C.S. casualties are over 4,000, many of whom are captured. Near Mobile, Alabama, Maj. Gen. Canby’s Union troops that have been moving up the eastern shore of Mobile Bay arrive at Spanish Fort, a fortification that protects the city of Mobile. Elsewhere, there is skirmishing in Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia.

On March 26, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s cavalry arrives at Petersburg, Virginia. Gen. Lee advises President Davis that he thinks it will not be possible to prevent the armies of Grant and Sherman from linking and that to leave his Confederate army where it is would be unwise. In Alabama, fighting begins at Spanish Fort, near Mobile, as Maj. Gen. Canby’s Union troops prepare to lay siege to the fort.

President Lincoln, visiting City Point, Virginia, with his wife Mary and son Tad, on March 27 begins a two-day meeting aboard the sidewheel steamer River Queen with Lt. Gen. Grant, Maj. Gen. Sherman (who has come from Goldsboro, North Carolina) and Rear Adm. Porter, to discuss strategy and his ideas as to what postwar reconstruction should entail. Sherman will later say that, at the meeting, Lincoln said that as soon as Southerners laid down their arms, he would be willing to grant them full citizenship rights. Some 45,000 Federal soldiers are besieging Spanish Fort, defended by 10,000 Confederates. The fort protects the eastern approach to the city of Mobile.

Two cavalry actions occur on March 28. Union Brig. James Wilson’s cavalrymen battle Confederates at Elyton, Alabama, as they wend their way toward Selma. In western North Carolina, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman’s Union cavalry fights Confederates at Snow Hill and Boone.

On March 29, Lt. Gen. Grant orders Maj. Gen. Sheridan’s cavalry and some infantry to try to turn the Confederate right flank southwest of Petersburg. Anticipating the move, Gen. Lee sends infantry under Maj. Gen. George Pickett and cavalry under Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee westward to block any Federal moves. The two sides clash at two separate locations, and the federal movements are stopped. Heavy rains begin to fall in the evening, halting most activity.

On March 30, heavy rains continue to hamper Union efforts to turn the right flank of the Confederate defensive lines west of Petersburg, Virginia. The Federals do make a thrust at Five Forks, 12 miles southwest of Petersburg, but Maj. Gen. Fitz Lee’s cavalry turns it back. At Montevallo, Alabama, around 52 miles north of Selma, Union Brig. Gen. James Wilson’s troopers face heavy resistance from the significantly outnumbered cavalrymen of Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. In Virginia, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early — back in Richmond after escaping from the devastating loss earlier in the month at Waynesborough, Virginia, at the hands of Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Union cavalry — is relieved of command by Gen. Robert E. Lee. This despite Early having kept Union troops tied up in the Shenandoah Valley and away from Petersburg for months. Lee, unable to ignore the recent string of devastating losses suffered by Early’s troops, a stated lack of confidence in Early by Virginia’s governor, and comments in the press and by other commanders that Early’s losses have made him an unacceptable leader to the troops, tells him to go home and wait. “While my own confidence in your ability, zeal and devotion to the cause is unimpaired,” writes Lee, “I have nevertheless felt that I could not oppose what seems to be the current of opinion.”

On March 31, a Union force — cavalry under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan and infantry under Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren — launches an assault on Confederate defenses at White Oak Road and Dinwiddie Court House, about 5 miles southeast of Five Forks, Virginia, southwest of Petersburg. Although outnumbered, the Confederates fend off the attack. Later that night, Maj. Gen. Pickett, feeling that the Union numbers are too overwhelming, orders his Confederates to withdraw to Five Forks. In Alabama, having broken through the opposition of Forrest’s Confederate cavalry, the Union troops of Brig. Gen. James Wilson take and occupy Montevallo and destroy iron furnaces and collieries.