May 1865

By Phil Kohn

Phil Kohn can be reached at USCW160@yahoo.com

On May 1, 1865, President Andrew Johnson orders the appointment of Army officers to act as a military commission to try those accused of the conspiracy to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his retinue, along with an armed escort of Confederate cavalry, continue to flee southward, reaching Cokesbury, South Carolina, about 80 miles west-northwest of Columbia. The plan is to reach Florida and, from there, sail to Texas.

Jefferson Davis and his party reach Abbeville, South Carolina, around 14 miles southwest of Cokesbury, on May 2. The group is uncertain of how it should proceed. Some opine that they should simply surrender themselves to Federal authorities, while others suggest finding refuge in a foreign country. Yet others propose continuing the struggle from west of the Mississippi River. Davis seems to favor the latter strategy, most of his advisors dissuade him from this option and convince him that it is time to stop fighting. He agrees: “All is lost.” The group continues moving southward towards Florida.

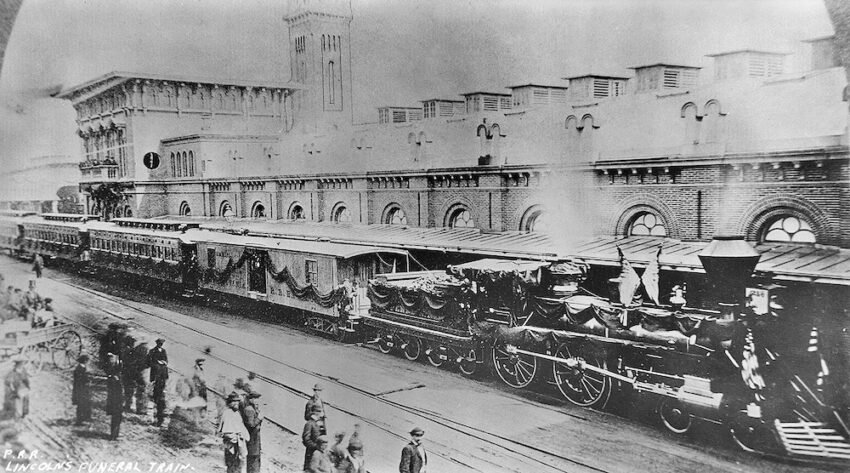

Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train, after a long and circuitous journey, on May 3 reaches Springfield, Illinois, where the remains of the assassinated president are to be buried. In South Carolina, Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin separates himself from President Davis’s party to travel on his own. He succeeds in reaching Florida and, finally, Great Britain, via a very circuitous route through the Bahamas and Cuba. Benjamin rejoins his wife and daughter, who have been in France since prior to the war, and becomes a barrister (lawyer) in the U.K. He never returns to North America.

On May 4, at Citronelle, Alabama, Maj. Gen. Edward Canby accepts the surrender of all Confederate forces under the command of Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. Canby offers Taylor the same terms as were given to Robert E. Lee, except that Taylor will be permitted to use railways and transport ships to return his men to their homes. On the same day, in the North, Connecticut becomes the 22nd state to ratify the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which will ban slavery in the U.S. A total of 27 ratifications (75%, or 27, of the 36 states) are needed for the amendment to become law. West of the Mississippi River, the fighting goes on. There is skirmishing between Union and Confederate forces near Lexington, Missouri, in the west-central part of the state, as well as in Arkansas and Alabama. The body of Abraham Lincoln is interred at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

Aware that Union cavalry is tracking — and gaining on — President Jefferson Davis’s retinue, Maj. Gen. John Breckenridge, Confederate Secretary of War, departs from Davis’s group with a small party on May 5 to create a diversion. Successfully eluding capture, Breckenridge manages to get to Florida and then Cuba, from where he reaches Europe. Davis dismisses the cavalry escorting him and his party, except for 10 troopers, hoping it will make escape more practicable.

U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton on May 6 officially appoints the commissioners who are to try the Lincoln assassination conspirators. Chief prosecutor is to be Brig. Gen. Joseph Holt, Judge Advocate General of the U.S. Army. Maj. Gen. David Hunter will preside over the commission. The ironclad Confederate raider CSS Stonewall arrives at Nassau, Bahamas, from Europe, on its maiden voyage as a Confederate vessel. (Stonewall was purchased from the Danish navy.) The ship soon leaves port, headed for Cuba. At Macon, Georgia, Union Brig. Gen. James Wilson announces a $100,000 reward for the capture of Jefferson Davis.

Before dawn on May 7, 110 pro-Confederate guerrillas ride into Kingsville, Missouri, about 45 miles southeast of Kansas City, where they sack the town and burn five houses.

On May 8, Union and Confederate troops skirmish near the hamlet of Readsville, in central Missouri, around 30 miles northeast of Jefferson City, the state capital. It is likely that the Confederates are guerrillas.

In a meeting on May 9 with the governors of the western Confederate states, Gen. E. Kirby Smith announces that, despite Lee’s surrender in Virginia, his own Army of the Trans-Mississippi remains intact, and he intends to continue the fight. At Dublin, Georgia, about 50 miles southeast of Macon, in the central part of the state, President Jefferson Davis, still fleeing southward, meets his wife, Varina, who has been traveling separately. She joins her husband’s small and diminishing band of fugitives. In Alabama, Confederate Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest disbands his troops. (They were included in the surrender by Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor on May 4.) He tells his troopers to dismiss all thoughts of further resistance wherever they may end up.

May 10 is a day full of activity. Confederate President Jefferson Davis, his wife Varina, Confederate Postmaster General John Reagan, Burton Harrison, President Davis’s secretary, and a few others are captured by a detachment of the 4th Michigan Cavalry near Irwinville, Georgia. (Contrary to political cartoons and newspaper stories indicating that Jefferson Davis was trying to elude capture in women’s clothing, he was actually wearing male garb, covered by a loose-sleeved, waterproof cloak and had a black shawl over his head to protect him from the rain that was falling when he was caught.) The captives are sent to Nashville, Tennessee, under heavy guard. Davis is subsequently transferred to Richmond, Virginia, and, finally, to Fort Monroe, in Hampton, Virginia, at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula. In Kentucky, Confederate guerrilla William C. Quantrill is mortally wounded in an ambush by U.S. troops at Taylorsville, near Louisville. Quantrill and a few dozen men had been depredating in the area. Attempting to escape on horseback, he is shot in the back and paralyzed. Taken by wagon to a military prison hospital in Louisville, Quantrill dies of his wounds on June 6, at the age of 27. At Waynesville, North Carolina, Confederate Col. William H. Thomas surrenders his Thomas Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders to Union forces. The 1,200-man Legion — including 400 Cherokees — is the last large Confederate unit to surrender in the East. At Tallahassee, Florida, Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones surrenders his Confederate command. In Washington, D.C., President Andrew Johnson declares that armed resistance to the authority of the Federal government can be considered “virtually at an end.”

On May 11, 300 Union troops cross over to the Texas mainland from Brazos Island, off the coast, for the purpose of occupying Brownsville. Rumor has it (erroneously) that the Confederates are evacuating the city. At Chalk Bluffs, in the extreme northeast corner of Arkansas, Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson, of the Missouri State Guard, surrenders the 6,600 men of his command in the Northern Sub-District of Arkansas to Federal troops sent from St. Louis, Missouri. (Although he was never mustered into Confederate service, Thompson often commanded Confederate regulars as well as his guerrilla band known as “Swamp Rats” in numerous successful operations in Missouri and Arkansas throughout the war.) The Confederate raider CSS Stonewall arrives at Havana, Cuba, where the vessel’s captain, Lt. Thomas Page, CSN, learns that, for all practical purposes, the U.S. Civil War has ended.

The Union force making its way to occupy Brownsville, Texas, on May 12 runs into 190 Confederates posted outside of town, and the Battle of Palmito Ranch begins. The fighting ebbs and flows, with the Federals first pushing the Southerners back. A rally by the Confederates later in the afternoon finally forces the Federals to withdraw from the field. Both sides call for reinforcements. In Washington, D.C., the eight defendants being tried for conspiracy resulting in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln plead not guilty. The taking of testimony begins. At the White House, President Andrew Johnson appoints Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard to head the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands. The bureau, which supervises extensive tracts of land in the South that have been confiscated by Union forces, is responsible for the care of Southern refugees from the war and helping former slaves adjust to their freedom.

At Palmito Ranch, outside of Brownsville, Texas, both sides have been reinforced and, on May 13, the fighting once again begins. The Union force has received 200 additional men, for a total of around 500. Col. John “Rip” Ford has arrived with 110 Confederate cavalry, bringing the number of Southerners to 300. However, Ford has also brought along six artillery pieces, said to have been provided by the French Army garrison at Matamoros, Mexico, directly across the Rio Grande from Brownsville. Aggressive offensive moves by the Confederates — and the artillery — make the difference, and the Union troops are forced to retreat. The fight is often considered the last battle of the Civil War and is, ironically, a Confederate victory. As few as 4 and as many as 40 Union troops are killed, 12 are wounded and 101 are captured. For the Confederates, 5 or 6 are wounded and 3 are captured. Some 580 miles to the northeast of Brownsville, at Marshall, Texas, the governors of Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana and a representative of the Texas governor meet with Gen. E. Kirby Smith and other high-ranking military officers to discuss strategy. The governors present possible terms of surrender that they strongly urge Smith to seek. Brig. Gen. Joseph “Jo” Shelby and other officers present threaten to arrest Smith — whom they believe favors surrendering — if he doesn’t continue fighting.

Despite President Johnson’s declaration that armed resistance has virtually ended, Federals and Confederates skirmish along Little Piney Creek, in Missouri, on May 14.

On May 15, several U.S. warships, including the monitors USS Monadnock and USS Canonicus, arrive outside Havana Harbor, in Cuba, where the Confederate raider CSS Stonewall is anchored. As Cuba is a Spanish possession, no action is initiated against the Southern vessel. At his headquarters at Shreveport, Louisiana, Gen. E. Kirby Smith receives a message from Union Maj. Gen. John Pope offering him the choice of unconditional surrender or “violent subjugation.” Rejecting Pope’s overture, Smith makes plans to move his headquarters to Houston, Texas, a more-secure venue.

Confederate units in western and southern Florida begin surrendering to Union forces On May 17. The same day, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan is given command of 50,000 U.S. troops west of the Mississippi River and south of the Arkansas River, with orders to clean up the rebellion in the Trans-Mississippi.

Lt. Thomas Page, CSN, captain of the ironclad Confederate commerce raider CSS Stonewall surrenders his vessel and crew to Spanish authorities at Havana on May 19. He sells the ship to the Spanish for $16,000 to pay off his crew. (Spain will subsequently turn the vessel over to the U.S., which reimburses Spain the purchase price. The vessel is moved to the U.S., where it is laid up at the Washington Navy Yard. In 1867, Japan, looking to modernize its navy, purchases the ironclad for $400,000, renaming it Kotetsu [which means “ironclad” in Japanese].)

Former Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory is captured near La Grange, Georgia, on May 20. He is transported to Fort Lafayette, in the Narrows of New York Harbor, where he will be held until his release in March 1866.

On May 22, President Johnson announces that, effective July 1, commercial restrictions are to be lifted from Southern ports, except for four in Texas: Brazos Santiago, Brownsville, Galveston and LaSalle. In addition, restrictions will be lifted on all commercial trade east of the Mississippi River, except for contraband of war. In Virginia, Jefferson Davis, having been brought from Tennessee, is imprisoned at Fort Monroe, in Hampton, Virginia. (Released two years later on $100,000 bail, Davis is never brought to trial. This is in part due to uncertainty over what exactly to try him for and concern that acquittal by a jury on a charge of treason would validate the constitutionality of secession. In February 1869, U.S. Attorney General William Evarts announces that the U.S. government is no longer prosecuting Davis.)

While Federal troops skirmish with Confederate guerrillas near Waynesville, Missouri, on May 23, the roughly 80,000 soldiers of the Army of the Potomac, headed by Maj. Gen. George Meade, march along Pennsylvania Avenue through the heart of Washington, D.C., in a Grand Review past throngs of cheering Washingtonians.

The next day, May 24, it is the turn of the 65,000 men of the Western Armies under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to march in Grand Review in Washington, D.C. However, on either day, not even one of the 175 regiments of Colored Troops (roughly, more than 178,000 men) that served in the U.S. Army during the war is included in the Grand Review. Skirmishing continues in Missouri.

On May 25, 300 people are killed at Mobile, Alabama, when a warehouse containing 200 tons of captured Confederate ammunition explodes. Fires follow the explosion, and the entire northern part of the city is left in ruins. Losses are estimated in the vicinity of $5,000,000. No official cause of the blast is ever determined, but many people feel it is the result of carelessness by workers moving wheelbarrows full of live ammunition around.

In New Orleans, Louisiana, on May 26, Lt. Gen. Simon Buckner, acting for Gen. E. Kirby Smith, meets with a representative of Maj. Gen. Edward Canby to discuss the surrender of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department. The two agree on conditions basically the same as offered to Robert E. Lee at Appomattox. Buckner will bring the terms to Kirby for approval. Back in Texas, Brig. Gen. Jo Shelby, remnants of his Iron Brigade and other Confederate officers repudiate the potential surrender agreement. They declare their refusal to surrender and decide they will disperse into Mexico or the Far West in order to continue the struggle.

On May 27, President Johnson orders the release of most people who had been imprisoned by the military during the war. In Louisiana, Union troops surprise a small group of Confederates at Bayou du Large, near Houma, around 60 miles southwest of New Orleans. The Confederates escape into the swamps but lose their weapons and provisions.

The Confederate raider CSS Shenandoah, sailing in the Sea of Okhotsk, around 620 miles north of the Kurile Islands, on May 28 captures and burns the U.S. whaling bark Abigail, out of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Abigail is the first U.S. vessel captured since Shenandoah departed from the Caroline Islands on April 10, and the 14th ship captured since Shenandoah began raiding in October 1864.

On May 29, President Johnson grants a general amnesty and pardon to all who participated in the rebellion, although there are a significant number of exceptions as to who can receive the benefits. Among those proscribed: high-ranking Confederate officials — civilian and military — and wealthy individuals, primarily planters, owning property worth $20,000 or more. (Most of these, however, later receive individual pardons at some time or another.) To qualify for a pardon, an individual must swear a loyalty oath, promise to uphold the Constitution and obey all laws, and renounce slavery. Once this is done, all the individual’s property rights (except those pertaining to slaves) are to be restored. This aspect of the amnesty will have significant ramifications. Because some of the land confiscated by the Union Army has already been distributed to and is now being farmed by freed slaves and other refugees, having to return it to their previous owners will cause problems.

On May 30, Federal troops in Texas begin operations against guerrillas and former Confederates trying to flee into Mexico. These activities continue for several weeks.