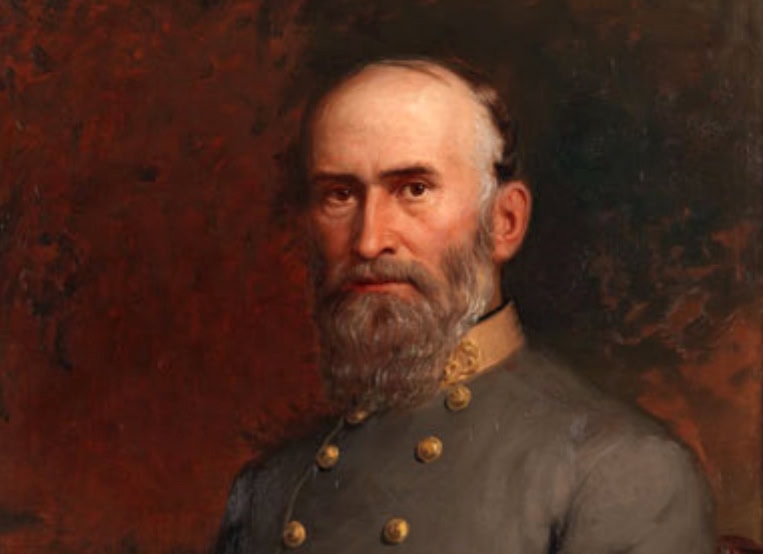

Confederate General Jubal Anderson Early. Painted in 1912 by J.W.L. Forster from a photograph taken in 1865. (Source: Virginia Museum of History and Culture)

July 1864

By Phil Kohn

Phil Kohn can be reached at USCW160@yahoo.com

On July 2, 1864, Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early — advancing northward down the Shenandoah Valley — enters Winchester, Virginia. Continuing northward, he splits his force, sending one group westward to Martinsburg, West Virginia, and the other eastward towards Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia.

Early’s Harper’s Ferry force confronts Union troops under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel on July 3 and drives them back.

In the face of Early’s Confederates, the Federal garrison abandons Harper’s Ferry on July 4. Panic spreads among Northern civilians, fearing yet another Confederate invasion. As the first session of the Thirty-Eighth U.S. Congress adjourns, President Lincoln pocket-vetoes the controversial Wade-Davis Bill concerning postwar reconstruction. Supported by ultraradical members of Congress, the bill, among other things, would impose harshly punitive conditions on a defeated South and would transfer control of reconstruction from the president to Congress. Lincoln was looking for a conciliatory approach, similar to what he had already instituted in the “returning” states of Louisiana and Arkansas.

The Harper’s Ferry group of Early’s Confederates crosses the Potomac River into Maryland near Sharpsburg on July 5 and begins moving eastward toward Frederick. In Washington, concern grows over Early’s movements. Grant begins transferring some troops to the capital city from Petersburg, Virginia, and militia are called out in Maryland, Pennsylvania and New York. The questions on everyone’s minds: Are the Confederates simply raiding or are they invading again? Second, where are they headed? Washington? Baltimore? Philadelphia? On the same day, U.S. Maj. Gen. A. J. Smith leaves La Grange, Tennessee, with 14,000 troops for a raid into Mississippi. Smith is under orders from Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to accomplish what Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis failed to achieve in June: “follow Forrest to the death if it costs 10,000 lives and breaks the Treasury.”

On July 6, Early’s other group (from Martinsburg, West Virginia) captures Hagerstown, Maryland, and demands $20,000 as reparations for raids in the Shenandoah Valley in June led by Union Brig. Gen. David Hunter, whose men Early’s troops had routed.

Federal reinforcements arrive in both Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland, on July 7, to bolster defenses in those cities. At this point, Union commanders do not know where Early and his troops are ultimately headed.

Acting against the express wish of President Jefferson Davis, Gen. Joseph Johnston responds to new flanking movements in Georgia by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Union force by moving his Army of Tennessee across the Chattahoochee River, closer to Atlanta on July 8.

Having reunited both “wings” of his force at Frederick, Maryland, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s 14,000 troops on July 9 run into some 5,800 hastily gathered, ill-trained Union defenders — invalids, railroad workers, garrison troops and militia — under Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace at the Monocacy River, southeast of Frederick. (Wallace — author of the novel Ben Hur after the war — was posted in Baltimore, Maryland, and was warned of Early’s approach toward Frederick by the president of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, whose railway agents had alerted him. Wallace then hastened to Frederick to organize the ragtag defenders.) Although ultimately defeated by the veteran Confederates (U.S. casualties number about 2,000; C.S. casualties around 700), the Union fighters manage to hold up the advance of Early’s force for a whole day. In Georgia, Gen. Braxton Bragg, President Davis’s military chief of staff, arrives to meet “in consultation” with Gen. Joseph Johnston. In the Atlantic Ocean, only 35 miles off the Eastern Shore of Maryland, the raider CSS Florida captures four U.S.-flagged ships.

By July 10, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Confederates are on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., engaging Union troops at several places, including Fort Stevens, one of the capital’s outer defensive positions, a mere five miles from the White House. The dome of the Capitol Building can be seen from Confederate lines. However, the previous day’s delay at Monocacy has allowed additional U.S. troops to be moved by ship from the vicinity of Petersburg, Virginia, to reinforce Washington.

On July 11, President Lincoln, along with his wife Mary and a party of others, visits Fort Stevens to observe the action. He climbs the parapet “to see what’s going on.” The 6-foot, 4-inch-tall Lincoln stands at the wall in his signature stovepipe hat and peers through field glasses at the Confederate lines. When a military surgeon standing next to the president is wounded by a Confederate sniper, Lincoln is unceremoniously pulled off the wall by an individual reported to be shouting, “Get down, you fool!” (Apocryphal stories identify the officer as Capt. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., a staff officer and later an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. However, various sources indicate that it is most likely Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, commanding officer of the three-corps-strong Washington Emergency Defense Force, who yanked the president down. Other stories say it is a private in an Ohio infantry regiment, the fort’s commander [Maj. Gen. Montgomery Meigs], a private in the Ohio National Guard and even a woman who was part of the entourage that accompanied Lincoln to Fort Stevens.) From Richmond, President Jefferson Davis sends a communication to Gen. Robert E. Lee: “Gen. Johnston has failed and there are strong indications that he will abandon Atlanta. . . . It seems necessary to relieve him at once. Who should succeed him? What think you of [Lt. Gen. John Bell] Hood for the position?”

Observing the arrival of yet more U.S. troops in the area, Jubal Early on July 12, decides to give up his assault on Washington. He orders his men to withdraw, and that night they head back toward the Shenandoah Valley. (There is considerable debate on whether Early could have taken Washington, D.C. Some of his subordinates have opined that he certainly could have. A newspaper correspondent in the city observed: “I have always wondered at Early’s inaction. Washington was never more helpless. Our lines . . . could have been carried at any point.” One of Early’s division commanders, Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, later wrote: “I myself rode to a point in those breastworks where there was no force whatever. The unprotected space was broad enough for the easy passage of Early’s army without resistance.” The consensus of opinion, however, is that even if Early did take the U.S. capital city, he didn’t have enough strength in numbers to hold Washington. Early also realized that his troops at this point were exhausted.)

Lt. Gen. Jubal Early and his troops spend July 13 crossing the Potomac River from Maryland into Virginia near Leesburg, Virginia. They are pursued by 15,000 Union troops in overall command of Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright.

On July 14, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s men have successfully crossed the Potomac River into Virginia. Maj. Gen. Wright ends his pursuit, informing Washington that he does not consider it prudent to pursue the enemy into Virginia. In Mississippi, the troops of Maj. Gen. A. J. Smith and Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest clash at Tupelo. In this instance, Forrest’s troops are actually under the command of Forrest’s commanding officer, Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee. The fight ends with a Federal victory on the field (U.S. casualties number 674, while Confederate casualties total 1,347, including Forrest, who is slightly wounded). The Union victory is wasted, however, as the next day, July 15, Smith, declaring that he’s “short on supplies,” starts heading back to Memphis, leaving Forrest free to again operate with impunity.

Lt. Gen. Jubal Early and his Confederates are moving back into the Shenandoah Valley on July 16 facing little opposition, except for some small rear-guard actions. In Georgia, Gen. Joseph Johnston is strengthening his fortifications, while planning to attack Sherman’s force if the opportunity presents itself. Meanwhile, Sherman’s Union troops are moving across the Chattahoochee River on pontoon bridges on their way towards Atlanta.

U.S. troops under Maj. Gen. Sherman begin encircling Atlanta on July 17. The Army of the Cumberland, under Maj. George Thomas approaches from the north, along Peachtree Creek. Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, farther east, also moves toward the city. East of Atlanta, in the vicinity of Decatur, is Maj. Gen. James McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee. The same day, President Davis, frustrated by Gen. Joseph Johnston’s lack of offense, relieves him as commander of the Army of Tennessee, replacing him with the aggressive Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood.

On July 18, President Lincoln calls for 500,000 more Union troops, to replace the great losses in the recent fighting in Virginia, as well as the 120,000-plus three-year-enlistees whose terms have expired and who have left the army.

Lt. Gen. William Sherman’s forces close in on Atlanta on July 19. The resistance is so feeble that Sherman wonders if the Confederates are retreating. Lt. Gen. Hood, however, is readying his Confederates for action, hoping to concentrate his force against one of the Union armies while it is separated from the others.

Hood launches an offensive led by Lt. Gen. William Hardee against Federals commanded by Maj. Gen. George Thomas, attacking them at Peachtree Creek on July 20. After two hours of fighting, the result: Confederate casualties: 4,796; Union: 1,779. Hood, not present at the fighting, tries to make Hardee the scapegoat for the defeat, alleging that Hardee delayed his attack for over three hours and once engaged, his men did not attack vigorously enough.

On July 21, after reinforcing Hardee’s corps, Hood once again sends him out to march south and then east towards Decatur to attack Maj. Gen. John McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee.

After a tiring, hot, night march, Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s 40,000 Confederates hit 30,000 of Maj. Gen. James McPherson’s Union troops between Atlanta and Decatur, Georgia, on July 22 in what is termed the Battle of Atlanta. The result is carnage. The Confederates suffer over 8,000 casualties (sources vary between 7,000 and 10,000 casualties), while U.S. casualties number 3,722, including the commander of the Union Army of the Tennessee, Maj. Gen. James McPherson. McPherson, riding on horseback from one place to another on the battlefield positioning troops, runs into Confederate skirmishers, who demand he surrender. When he bolts, attempting to escape, he is shot dead in his saddle. He is replaced by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard. Now effectively besieging Atlanta, Maj. Gen. Sherman directs his attention towards Lt. Gen. Hood’s — and Atlanta’s — supply lines.

At Petersburg, Virginia, work is completed on July 23 on a 511-foot-long tunnel under Confederate entrenchments dug by Union soldiers that had been coal miners. The tunnel extended from behind the Union siege line and ended around 20 feet below the Confederate positions. A gallery extended about 40 feet perpendicularly on each side of the entrance tunnel. The plan, championed and approved by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, is that the gallery and the far end of the tunnel will be packed with explosives that, when detonated, will blow a massive breach in the Confederate lines.

Back in the Shenandoah Valley, Jubal Early’s Confederates defeat Union troops led by Brig. Gen. George Crook on July 24 at Kernstown, near Winchester, Virginia. Confederate casualties are light, while U.S. casualties number 1,185. The Federals retreat to the north.

Following Crook and his troops, Early’s men catch up and engage on July 25 near Martinsburg, West Virginia, on the Potomac River. The Southerners are vanquished. Farther south, Lt. Gen. Grant tries to tighten his hold on Petersburg, Virginia, by sending troops against the railroads connecting the city and Richmond.

On July 26, U.S. Maj. Gen. George Stoneman leads a cavalry raid out of Atlanta on a mission to free Federal prisoners being held at Andersonville. The force makes it as far south as Macon (a bit more than halfway) when it is hit by Confederate cavalry under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, turned around and chased. Around 700 Federals are captured, including Stoneman, who becomes the highest-ranking Union prisoner of the war. He is held for about three months before being exchanged as the result of a personal request by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman.

In Alabama, a U.S. Navy flotilla under the command of Rear Adm. David Farragut conducts a reconnaissance of Mobile Bay on July 27.

Lt. Gen. Hood’s Confederates attack Union lines on the west side of Atlanta at Ezra Church on July 28. The advances are turned back at the expense of around 600 Federal casualties. Confederate casualties are as high as 5,000 or more. Hood’s aggressiveness is, so far, nothing less than a disaster for the Confederates.

Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s troops on July 29 once again cross the Potomac River into Maryland, near Williamsport, and cause panic among the citizenry. They engage in skirmishes and fighting at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, Hagerstown, Maryland and Mercersville, Pennsylvania.

On July 30, Early’s cavalry raids Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and demands $500,000 in greenbacks or $100,000 in gold as reparations for Federal arson committed in the Shenandoah Valley. When the city fathers don’t come up with the levy, the town’s business district is burned. On the same day, farther south, on the siege line at Petersburg, Virginia, the mine dug by miners in the Union army has been packed with four tons of gunpowder. Detonation of the explosives is set for 3:00 a.m., which comes and goes with nothing happening. Two volunteers enter the tunnel and find that the fuse has gone out. They relight the fuse, and at 4:45 a.m., the explosion under the Confederate lines sends flames, dirt, cannons, bodies and body parts 100 feet in the air and creates a crater 170 feet long by 70 feet wide by 30 feet deep. Some 280 Confederates are killed. The ensuing Union attack through the breach — the Battle of the Crater, as it comes to be known — is a disaster: 15,000 Union troops charge into the breach and down into the crater but then can’t get up the steep sides. Confederate defenders recover rapidly and begin firing downward into the tight mass of Federals packed into the crater, leading to 3,748 U.S. casualties. (An inquiry following the incident basically ends the career of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, who had championed the plan. He is sent on leave and never recalled to active service. He resigns from the army on April 15, 1865.)

President Lincoln, concerned about the safety of Washington, D.C., with Jubal Early’s forces seeming to roam freely, meets for five hours on July 31 with Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant at Fort Monroe, in Virginia, to discuss the problem. In response, Grant puts Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan in charge of Federal operations in the Shenandoah Valley, with orders to defeat Early and his Confederates.