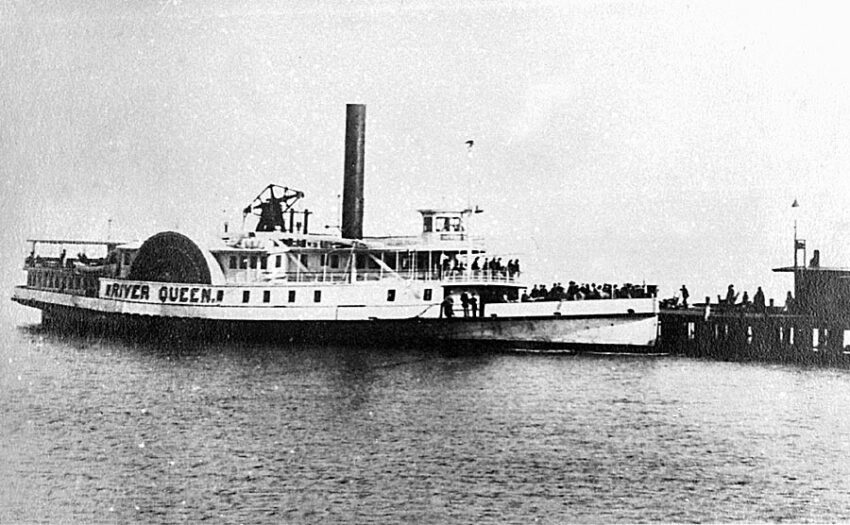

On Feb. 3, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln And Secretary of State William Seward met aboard the River Queen steamship with representatives of the Confederacy to discuss peace. [Public Domain/Wikipedia]

February 1865

By Phil Kohn

Phil Kohn can be reached at USCW160@yahoo.com

On February 1, 1865, after having been delayed by heavy rains, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army of 58,000 Federals begins moving. It splits apart on its northward journey into South Carolina: the right wing starts heading towards Charleston, while the left wing moves northwest towards Augusta, Georgia. Opposing are roughly 12,500 Confederates under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler around Augusta and another 10,000 under Lt. Gen. William Hardee at Charleston. The Confederates do not know, however, that Sherman’s real target is the state’s capital, Columbia. In the North, Illinois becomes the first state (of 27 needed) to ratify the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which will abolish slavery in the U.S. Within a week, 10 more states — Rhode Island, Michigan, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Missouri, Maine, Kansas and Massachusetts — approve the measure.

On February 2, President Lincoln leaves Washington for Fort Monroe, in Hampton, Virginia. He will meet with the Confederate peace commissioners tomorrow to discuss a possible end to the war. U.S. Secretary of State William Seward is already there.

Aboard the sidewheel steamer River Queen, moored in Hampton Roads, Virginia, off Fort Monroe, on February 3, President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward meet with Confederate representatives — Vice President Alexander Stephens, Senator Robert Hunter and Assistant Secretary of War John Campbell — to discuss peace, as well as a variety of other topics put forth by the Southerners. Among these are: a joint movement against Mexico and the French intervention there, and even a temporary stoppage to the fighting. Lincoln is negative to any ideas. Lincoln and Seward mention that Congress has passed the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery, and that it has gone out to the states for ratification. The Confederates ask what would happen if the Union were restored. Lincoln replies that if it is up to him, he’d be lenient in his policies, but he cannot speak for Congress. The meeting lasts four hours, is considered “friendly,” but accomplishes nothing because of Confederate insistence on independence without surrender and Lincoln’s intransigence on accepting nothing less than reunification under the authority of the Federal government.

Back in Washington, D.C., President Lincoln — with the idea of curtailing further bloodshed — on February 5 proposes a plan to his Cabinet to pay $400 million to the slave states if they will lay down their arms and agree to emancipation before April 1. The Cabinet is unanimously opposed and points out that, in any case, Congress would never approve the plan. The idea goes no further.

In Richmond, Virginia, President Jefferson Davis on February 6 reports to the Confederate Congress that the peace talks at Hampton Roads were a failure. He notes that Lincoln wishes unqualified submission as terms for peace. In South Carolina, fighting takes place at the Little Salkehatchie River and near Barnwell as Confederates continue to resist Sherman’s advancing columns.

Voters in Delaware reject ratification of the 13th Amendment on February 7. The same day, the three-day Battle of Hatcher’s Run, near Petersburg, Virginia, ends. Union casualties number about 1,500. Confederate casualties are unknown, but are likely around 1,000. Now, Union lines extend their farthest south and west of Petersburg, and Gen. Robert E. Lee’s roughly 46,000 Confederates must hold 37 miles of defensive positions.

In South Carolina on February 8, Maj. Gen. Sherman responds to a complaint from Confederate Lt. Gen. Wheeler that Union soldiers are wantonly destroying private property: “I hope you burn all your cotton and save us the trouble. All you don’t burn, I will. As to private houses occupied by peaceful families, my orders are not to disturb or molest them, and I think my orders are obeyed. Vacant houses being of no use to anybody, I care little about. I don’t want them destroyed but do not take much care to preserve them.”

On February 9, a “rump legislature” (comprising anti-secessionist legislators who were originally elected to the Virginia Legislature) — that has met at Alexandria, Virginia, since the start of the war and which claims to be loyal and the legitimate representative of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the Union — votes to ratify the 13th Amendment. The result is accepted by the U.S. State Department and Virginia, although technically still in rebellion, ironically becomes the 12th state to approve the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. By month’s end, 18 states will have ratified the amendment. On the same day, 20,000 Federal troops of XXIII Corps, led by Maj. Gen. John Schofield, who have come east from Tennessee, depart Alexandria, Virginia, for recently Union-captured Ft. Fisher, North Carolina, for an assault on Wilmington. Gen. Robert E. Lee officially assumes the position of general-in-chief of the Confederate Army.

Fighting breaks out around Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, on February 10. Confederates there — still not knowing if Sherman’s troops are coming their way — must maintain a readiness to defend against land or sea attacks. Capt. Raphael Semmes, CSN, former commander of the commerce raider CSS Alabama, is promoted to rear admiral and placed in command of the Confederate navy’s James River Squadron.

U.S. cavalry under Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick is dispatched from the left wing of Sherman’s army on February 11 to destroy a Confederate supply depot and a powder works at Augusta, Georgia. The attack is stopped and repulsed by troops under Maj. Gen. Joe Wheeler at Aiken, South Carolina, some 15 miles east of the objective.

In Washington, D.C., the electoral college meets on February 12. By a vote of 212-21, Abraham Lincoln is declared president of the U.S. for a second term.

In London, England, British Prime Minister Lord John Russell on February 13 lodges a complaint with U.S. representatives about U.S. activities on the Great Lakes in North America. Great Britain and authorities in its colony, British Canada, are upset at U.S. military buildups in the area. The U.S. government replies that the activities are necessary to counter and thwart raids by Confederates allowed to operate out of Canada, such as the assault on St. Alban’s, Vermont, in October 1864.

On February 14, the two wings of Sherman’s army begin converging and turn toward Columbia, South Carolina. Because of a remaining uncertainty of where Sherman is headed, President Davis urges Lt. Gen. William Hardee, in Charleston, along with Gen. Pierre Beauregard, who is there with him, to delay evacuating the military from the city as long as possible.

By February 15, Maj. Gen. Sherman’s troops are on the west and south banks of the Congaree River, opposite Columbia, South Carolina. The city is defended by cavalry troops under the command of Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton.

On February 16, Gen. Pierre Beauregard arrives in Columbia, South Carolina, from Charleston to meet with Lt. Gen. Hampton and assess the situation. It doesn’t take long until Beauregard sends a message to Gen. Lee, telling him that nothing can be done to save the state capital. By midafternoon, Beauregard departs and heads towards North Carolina. On the coast, at Charleston, Lt. Gen. Wiilliam Hardee realizes that although Sherman is heading for Columbia and not Charleston, the Union force is between him and possible Confederate reinforcements coming eastward from Augusta, Georgia. Hardee prepares to evacuate his troops northward from Charleston.

In South Carolina, the Columbia city fathers on the morning of February 17 ride out of town to meet with Maj. Gen. Sherman and surrender the state capital to him. The Union Army takes over the city. That night, fires erupt in several areas of Columbia; by morning, two thirds of the city has burned to the ground. Sherman says fleeing Confederates started the blazes, but townspeople and other Southerners blame Sherman and his “marauding army” for setting the fires. At Charleston, Lt. Gen. William Hardee evacuates his troops, including those located at Ft. Sumter, which has resisted Union bombardments and assaults for two and a half years. Hardee’s men head north towards Cheraw, South Carolina, some 150 miles to the north and 10 miles south of the North Carolina state line.

On February 18, Gen. Robert E. Lee, in a letter to Mississippi representative Ethelbert Barksdale, endorses a bill introduced by Barksdale in the Confederate House of Representatives that is being discussed and debated: arming slaves to fight as soldiers for the Confederacy. Lee tells Barksdale he believes that blacks would make efficient soldiers; he urges that they be allowed to fight as “free men.” In Columbia, South Carolina, Maj. Gen. Sherman orders that all railroad depots, supply houses and industrial facilities not burned in the previous night’s fires be destroyed. In North Carolina, U.S. Navy ships bombard Ft. Anderson, on the Cape Fear River south of Wilmington. Simultaneously, troops led by Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox land south of the city and head west, hoping to outflank Confederate defenders. In the Southern Hemisphere, after several days spent refitting, the raider CSS Shenandoah departs from Melbourne, Australia.

The Confederate House of Representatives, after long debate, on February 20 passes Barksdale’s bill that would authorize the use of slaves as soldiers. The next day, the Confederate Senate tables the measure for further discussion.

Gen. Lee on February 21 writes to Confederate Secretary of War John Breckenridge that if it becomes necessary to abandon Richmond, he plans to move his army to Burkeville, Virginia, about 60 miles to the southwest of Richmond and some 50 miles west of Petersburg. There, Lee states, he could make contact with Confederates in the Carolinas, and even possibly join forces to attack either Grant’s forces or Sherman’s individually, if the opportunity presented itself. In a letter to his wife, Marse Robert seems a bit more uncertain, writing that he expects Grant “to move against us soon” and that Sherman, in South Carolina, and Schofield, in North Carolina, “are both advancing & seem to have everything their own way . . .” In North Carolina, Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s Union troops reach Wilmington after a series of flanking maneuvers and successful engagements beginning from their arrival at Ft. Fisher days earlier. Gen. Braxton Bragg — squeezed between Cox’s troops to the west and, now, Schofield’s soldiers — orders his Confederates to withdraw from Wilmington and move to Kinston, North Carolina, about 85 miles to the north. Confederate 1st Lt. Jesse McNeill leads 62 partisan rangers from Moorefield, West Virginia, on a night raid into Cumberland, Maryland, which is held by a large Union garrison. His goal is to kidnap Maj. Gen. Benjamin Kelley, who had been responsible for the arrests of his mother, sister and brother. Not only does McNeill successfully extract Kelley from his hotel room, he and his men also capture Kelley’s superior, Maj. Gen. George Crook, another officer and two privates, all of whom are sent off to Richmond as prisoners of war. For his efforts, McNeill is praised by Gen. Robert E. Lee and promoted to captain.

On February 22, Federal soldiers enter Wilmington, North Carolina, unopposed, capturing 66 pieces of light and heavy artillery. Gen. Lee, general in-chief of the Confederate Army, names Gen. Joseph Johnston commander of Confederate forces in Tennessee, Georgia, Florida and South Carolina. The move is approved by President Davis. Johnston is ordered to concentrate his available troops as quickly as possible. Gen. Beauregard, who has been in ill health, is ordered to assist Johnston. In Kentucky, voters reject the 13th Amendment.

Heavy, persistent rains begin to fall in the Carolinas on February 23.

Maj. Gen. Sherman complains to Confederate cavalry commander Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton on February 24 that Confederate soldiers have murdered Union soldiers who were foraging. Hampton replies that he is unaware of the incident to which Sherman is referring but states he has ordered his men to shoot on sight any Northerners caught burning people’s homes. He adds: “This order shall remain in force so long as you disgrace the profession of arms by allowing your men to destroy private dwellings.” Gen. Lee expresses his concern to the Confederate War Department over the “alarming number of desertions that are occurring in the army.”

Gen. Joseph Johnston on February 25 officially assumes command (once again) of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, most of which is now in the Carolinas. His challenge is to try to stop Sherman with forces that are widely scattered: 10,000 under Hardee west of Fayetteville, North Carolina; a similar number under Wheeler near Augusta, Georgia; Bragg’s force, at Kinston, North Carolina; and roughly 5,000 men still on the way from Tennessee. In a communication, Johnston points out to Gen. Lee the difficulty of trying to concentrate these disparate troops. He adds that, including militia, cavalry and troops not heard from in a while, he only has between 20,000 and 25,000 men with which to defend against the oncoming Union forces, and that in his opinion, “these troops form an army too weak to cope with Sherman.” He suggests that he combine his force with that of Gen. Bragg in North Carolina.

Action in the Shenandoah Valley heats up on February 27, as Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, responding to orders from Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant, sends 10,000 Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt from Winchester, Virginia, to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad and the James River Canal, capture the city of Lynchburg, Virginia, and then, finally, join up with Maj. Gen. Sherman’s force.

On the final day of the month, Maj. Gen. Sherman’s 58,000 men are poised to continue their northward march into North Carolina.

“The Peacemakers” by George Peter Alexander Healy, 1868, depicts the historic 1865 meeting on the River Queen. Seated in the after cabin of the Union steamer, River Queen, are Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, President Abraham Lincoln, and Rear Adm. David D. Porter.

The White House Historical Association [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9359798