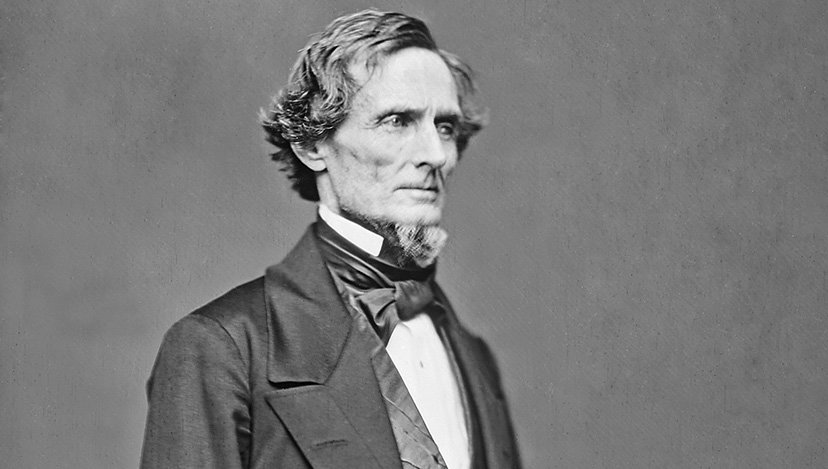

Jefferson David by Matthew Brady ca. 1859, one year before he became President of the Confederacy. (Library of Congress)

March 1864

By Phil Kohn

Phil Kohn can be reached at USCW160@yahoo.com

On March 1, 1864, the Union cavalry raid on Richmond, Virginia, to free prisoners of war closes in on the Confederate capital. Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick and 3,000 men approach from the north, with Col. Ulric Dahlgren and 500 troopers coming from the west. Word of their impending arrival has preceded them and a hastily thrown-together force of civilians, wounded soldiers and veterans take up defensive positions. Kilpatrick runs into these defenders and, after light skirmishing, decides it is a major Confederate force and withdraws, puzzled that Dahlgren has not rendezvoused with him as planned. Dahlgren, meanwhile, gets to within 2-1/2 miles of Richmond by nightfall, also against ever-increasing resistance. Judging he can go no farther at night and realizing that Kilpatrick has not achieved his goal, he gives up the attempt on the city and orders a retreat, aiming to rejoin Kilpatrick’s main body. In Washington, D.C., President Lincoln nominates Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant for promotion to the newly revived rank of lieutenant general.

On March 2, the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raiders continue their retreat, with Dahlgren’s force, having split into two groups, trying to catch up with Kilpatrick. All the Union troopers are closely and strongly harassed by Confederate cavalry. Around 11 p.m., Dahlgren and 100 troopers blunder into an ambush: Dahlgren is killed and 92 of his men are captured. Two highly controversial documents are found on Dahlgren’s body. One, unsigned, says: “. . . once in the city it must be destroyed and Jeff. Davis and Cabinet killed.” The other, signed by Dahlgren — a seeming address to his men — echoes the first document. The papers are quickly forwarded to Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, in charge of Confederate cavalry in the Richmond area, who immediately carries them to President Davis. After reading them, Davis directs Lee to bring the documents to Secretary of War James Seddon, who has their contents published in several newspapers. Outrage spreads through the South. Once the information gets to the North, newspapers and some officials there declare that the documents are forgeries. A subsequent Federal investigation is inconclusive, but U.S. Maj. Gen. George Meade, commanding the Army of the Potomac, sends a communication to Army of Northern Virginia commander Gen. Robert E. Lee reassuring him that no one in the government or in the army “had authorized, sanctioned or approved” the actions indicated. (Whether Meade’s statement is factual or a coverup has been long debated but never determined with certainty. Subsequent study seems to indicate that the documents are, in fact, genuine, but who generated them — Kilpatrick, Dahlgren himself or even President Lincoln — is not known. At least one historian points to the “unscrupulous” Edwin Stanton, the U.S. Secretary of War, as the author. Adding substance to that suspicion, Stanton, after the war orders that the original Dahlgren papers [recovered by the Union when Richmond fell] be turned over to him, at which time he destroys them.) In any case, the failed raid is a Union disaster, costing 340 men, 583 horses and a large number of weapons, as well as damaging the honor of the U.S. in the South and in Europe when details of the “barbaric” orders are made public by the Confederacy.

In Washington, D.C., the U.S. Senate on March 4 confirms Sen. Andrew Johnson as the military governor of Tennessee, his home state. A Democrat, Johnson is the only member of the Senate from a seceded state who remained in the Senate.

Confederates attack the Union garrison at Yazoo City, Mississippi, on March 5. The next day, the U.S. troops pull out, with the Southerners retaking the city.

President Abraham Lincoln and Maj. Gen. Ulysses Grant meet face-to-face for the first time, at a White House reception on March 8.

At a ceremony in Washington, D.C., on March 9, President Lincoln presents Ulysses S. Grant with his commission (dated to March 2, 1864) as the U.S. Army’s sole lieutenant general, a rank held previously by only two men: George Washington and Winfield Scott. After his meeting with the president, Grant immediately leaves for Brandy Station, Virginia, where the Army of the Potomac is located.

On March 10, in Virginia, Lt. Gen. Grant meets with Maj. Gen. George Meade. Grant decides that while his headquarters will reside with the Army of the Potomac, Meade will remain the army commander. Farther southwest, the Union begins its Red River Campaign under overall command of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks. Among the goals are to control the Red River, which flows through northwest Louisiana and to invade and occupy east Texas. Some 17,000 troops under Maj. Gen. William Franklin move up the Red River aboard 40 transports from winter quarters at New Iberia, Louisiana. Meanwhile, 10,000 U.S. troops from Maj. Gen. Sherman’s command, led by Brig. Gen. A. J. Smith, sail down the Mississippi from Vicksburg aboard 26 transports. Reaching the juncture with the Red River on March 12, they are met by 13 ironclads and 7 gunboats commanded by Rear Adm. David D. Porter. Soon, Franklin’s force arrives and the flotilla sets off upriver. Two worries vex Maj. Gen. Banks: the river’s water level is extremely low and Fort DeRussy, in Avoyelles Parish, south of Alexandria, in east central Louisiana, blocks the way.

On March 12, in Washington, D.C., Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant officially assumes the office of commander-in-chief, U.S. Army. Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, who formerly held that position, assumes the post of chief of staff. Grant now oversees over 860,000 troops, including six major field armies — three in the east and three in the west. This does not count the 500,000 new draftees called up by President Lincoln in February. Confederate strength (all troops): about 460,000.

After an overnight, overland march, Brig. Gen. A. J. Smith’s Union troops on March 14 overwhelm Fort DeRussy, capturing 210 prisoners and several guns. Meanwhile, the Federal fleet bursts through a dam nine miles below and heads up the Red River. In Washington, D.C., President Lincoln issues an order for the drafting of 200,000 men for service in the U.S. Navy.

Federal gunboats reach Alexandria, Louisiana, on March 15, and hold the town until army units (on ships and on foot) get there the next day.

On March 16, Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest leads two Confederate divisions, totaling 7,000 men, on an expedition into western Tennessee and Kentucky.

In Nashville, Tennessee, on March 17, Lt. Gen. Grant meets with Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman — now to be commander in the West — to discuss their plans for dealing with Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston’s Army of Tennessee, currently in Dalton, Georgia. Grant also publicly announces that his headquarters will be in the field and, until further notice, with the Army of the Potomac.

The Georgia legislature on March 19 gives a vote of confidence to President Davis and suggests that after any subsequent significant Confederate victory, a peace proposal should be made to Washington, D.C., predicated on Southern independence.

On March 20, Maj. Gen. Forrest’s Confederates besiege Jackson, Tennessee. Forrest sets up his headquarters in the town four days later when the Union garrison surrenders.

Part of the Union Red River force on March 21 defeats Confederate defenders at Henderson’s Hill, Louisiana, capturing 250 men, 200 horses and four guns. This loss severely limits the Southerners’ scouting abilities.

Union Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele on March 23 departs southward from Little Rock, Arkansas, with 8,500 troops, intending to link up with Maj. Gen. Banks’s Red River force at Shreveport, Louisiana. Back in Washington, D.C., after meeting with Sherman, Grant begins preparations for executing a significant plan he has developed: the simultaneous advance of all his armies.

On March 24, Bedford Forrest’s Confederates capture Union City, Tennessee, then conduct raids on Paducah, Kentucky, on the Ohio River (on March 25), and Columbus, Kentucky (on March 27). Also on March 24, Maj. Gen. Banks arrives at Alexandria, Louisiana. The Union commander of the Red River Campaign receives two pieces of distressing news. The first is that he must return the 10,000 troops under Brig. Gen. A. J. Smith to Maj. Gen. Sherman by April 15, so they can be used in a planned campaign against Atlanta. The second is that water levels in the Red River are so low that his fleet may not be able to move away from Alexandria. Nonetheless, he orders his troops to begin moving towards Shreveport, Louisiana, some 135 miles to the northwest.

U.S. Maj. Gen. Sherman on March 26 sends a cavalry force out from Memphis to stop the raiding of Forrest’s Confederates. Aware of Sherman’s move, Maj. Gen. Forrest moves his force out of Paducah, Kentucky, and heads towards Fort Pillow, on the Mississippi River in Tennessee, 135 miles to the southwest and some 50 miles northeast of Memphis.

On March 28, in Charleston, Illinois, a riot breaks out between Federal soldiers on leave and a mob of about 100 “Copperheads” (Democrats opposed to Lincoln’s war policy). Troops are called out to restore order in the worst anti-war unrest since the New York City Draft Riots in 1863. Before the violent outbreak is quelled, five people die and 20 are injured. In Bonham, in north Texas, Confederate Brig. Gen. Henry McCullough arrests guerilla commander Col. William Quantrill on charges of ordering the killing of a Confederate Army major. Since their arrival in Texas in October 1863, Quantrill’s irregulars have been preying indiscriminately on the citizens of Fannin and Grayson Counties, to the point where regular Confederate troops had to be assigned to protect residents from the guerillas. (In 1861, voters in those two counties had voted 2-1 against secession.) Later in the day, Quantrill escapes confinement and heads for his camp at Sherman, Texas, about 30 miles to the west. Quantrill and his men break camp and — pursued by around 300 Confederate and Texas state troops — head north, crossing the Red River into the Chickasaw Nation of Indian Territory, where they elude capture. Farther downstream along the Red River, Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor, commanding the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department’s District of West Louisiana, begins massing Confederate troops to resist the advance of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’s federal forces up the river.

Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele’s Union force on March 29 reaches Arkadelphia, Arkansas, the former Confederate state capital (which has again moved, to Washington, in the far southwest corner of the state). On the same day, the Union cavalry force sent to stop Forrest’s raiding is soundly defeated by his troops at Bolivar, Tennessee, and skedaddle back to Memphis. Forrest’s force returns to its Jackson, Tennessee, headquarters the next day.

On March 31, Banks’s combined Red River force of 27,000 troops, 66 transports and 20 warships reaches Natchitoches, Louisiana, just 75 miles downriver from Shreveport, the headquarters of the Confederacy’s Trans-Mississippi Department. Ahead of Banks’s troops, Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor’s Confederates burn cotton fields along the banks of a 10-mile stretch of the Red River.